A reform of the Criminal Code of Canada in 2018 changed something you’ve probably never thought about: duelling is no longer considered a crime in Canada. Here’s a look back at this often-deadly practice, as popular with the King of France’s musketeers as with politicians and other notables.

For reasons of honour

Throughout history, the reasons for challenging someone to a duel have varied: insults, business disputes, political conflicts and, of course, matters of the heart.

Duels were commonplace in 16th-century France, even though some kings had formally forbidden them. While duelling was seen as a noble way of restoring honour in the face of wrongs, it soon became a convenient excuse to fight a rival. French governments soon realized that the main consequence of duelling was to needlessly spill the blood of young nobles eager to fight. However, duellists persisted in their activity in defiance of the possible penalties: forfeiture of nobility, infamy, confiscation of property, or even the death penalty.

From New France to the Canadian Confederation

The taste for duelling spread across the Atlantic to New France. The first duels were recorded in 1646 and continued after the British Conquest. Duels in New France were fought exclusively with swords and mainly by soldiers and officers. Note that duels did not necessarily end in death but often in severe or minor injury.

After the Conquest of New France and the new British regime in 1763, duelling continued in Canada, but the pistol replaced the sword as the weapon of choice.

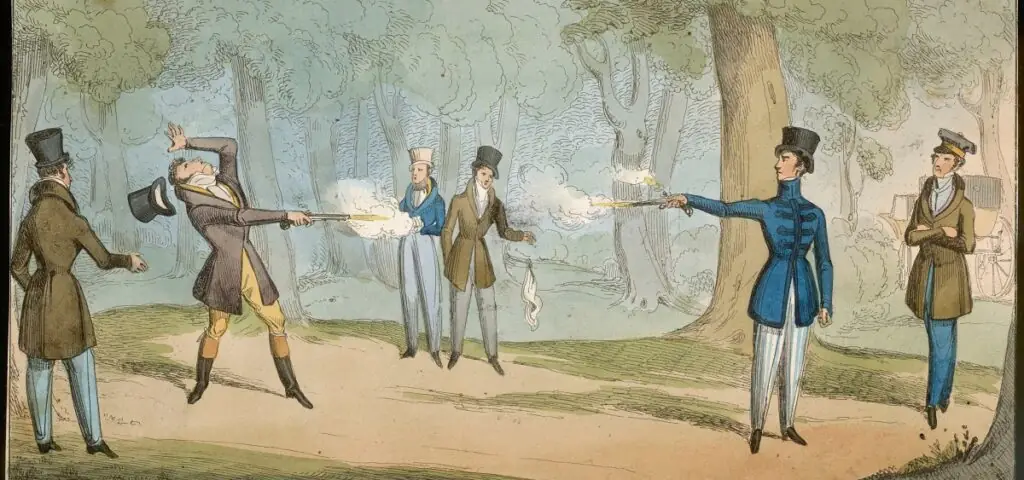

The way to challenge someone to a duel also changed: if a man felt another man had offended him, he would send a letter called a “cartel” demanding reparation. If the offended man was not satisfied with the response, the two duellists would meet at a designated location for a pistol duel in front of witnesses. Before the duel, the witnesses would make a final attempt to reason with the duellists to settle the dispute without bloodshed. Only as a last resort would the two men go ahead with the duel, shooting at each other from a predetermined distance.

Around the 19th century, duelling ceased to be a military affair and became increasingly common among notables and the upwardly mobile: journalists, doctors, lawyers, and politicians, among others.

Fortunately, there have been no reports of duels between women on Canadian soil.

Variable penalties

Sentences for duelling were often severe but were not uniformly applied. In New France, death sentences for duels between soldiers were commonplace, but courts were more lenient towards officers and gentlemen. For these, the courts felt that fines or reassignments were more than sufficient.

After the British Conquest, duels were still officially forbidden, but the courts were lenient towards the accused. Acquittals were easily granted if it was felt that the duel had been conducted with honour — whether or not someone had died.

In 1892, the first Criminal Code of Canada provided a sentence of three years’ imprisonment for anyone who challenged someone to a duel or encouraged someone to fight a duel. The final version of that provision, repealed in 2018, reduced the penalty to less than two years and criminalized accepting a duel. This doesn’t mean that, since 2018, it’s okay to challenge anyone to a duel! Even though challenging someone or accepting a duel are no longer crimes, the consequences – such as injuring or killing your opponent — are still criminal.

Memorable duels

The last duel to the death in Canada took place in May 1838 at Rivière-Saint-Pierre (now Verdun) in Montreal. Canadian Volunteer Captain Robert Sweeny killed Major Henry Warde in a pistol duel. The motive: Major Warde had sent a letter to Sweeny’s wife, professing his love for her. Numerous credible witnesses watched the duel, yet the jury concluded that Major Warde had died from a bullet fired by an unknown person. Sweeny avoided conviction thanks to the jury’s complicity, but he died two years later, racked with remorse for having killed a man.

The last known non-lethal duel on Canadian soil occurred in 1873 in Newfoundland, which had not yet joined the Canadian Confederation. Two former great friends, Augustus Healey and Denis Dooley, challenged each other to a pistol duel over their love for the same woman, a certain Miss White. A slight twist: the witnesses had no intention of letting the two friends kill each other, so the pistols contained no real bullets. After the blank shots were fired, Dooley fainted, and Healey was panic-stricken, convinced that he had killed his opponent. Once the trick was revealed, Healey and Dooley settled their differences in a fistfight, with Healey winning.

And how about Miss White? Discouraged by such childish behaviour, she chose neither of the two duellists and married another man a few years later.