The Judicial System

Courts of First Instance

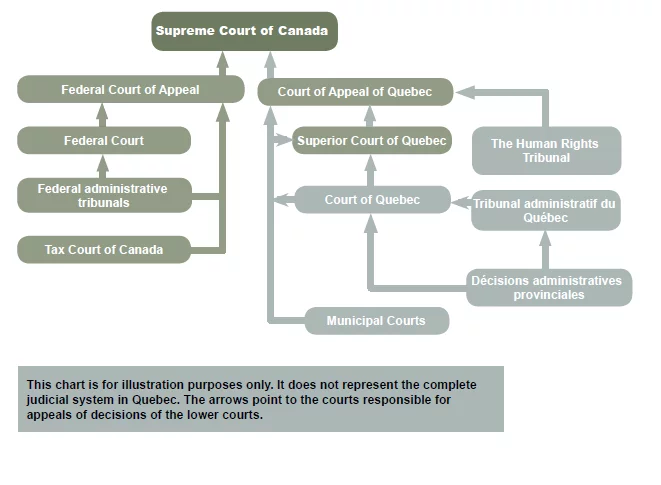

Courts of first instance are the first courts to hear a case. They hear witnesses and deal with evidence.

In Quebec, these courts include the municipal courts, Court of Québec, Superior Court, Federal Court and The Human Rights Tribunal.

Municipal courts

Municipal courts deal with two kinds of cases:

- civil cases where municipalities try to claim money owed by residents for taxes or permits

- penal cases where residents are fined if they break municipal laws or the Highway Safety Code.

In some cities, municipal judges can also hear criminal cases dealing with less serious offences, such as assault or impaired driving.

Court of Québec

The Court of Québec includes three divisions:

- the Civil Division (which includes the Small Claims Division)

- the Criminal and Penal Division

- the Youth Division

The Civil Division hears cases involving claims of less than $100,000. Where the sums at stake are between $75,000 and $100,000, the person who initiates the proceeding may choose to file it before the Civil Division of the Court of Québec or before the Superior Court.

The Court of Québec also hears appeals from decisions of some administrative tribunals, such as the Tribunal administratif du logement (TAL, formerly Régie du logement or rental board)

Cases involving $15,000 or less go to the Small Claims Division (often called small claims court). In this division, people cannot be represented by a lawyer.

The Criminal and Penal Division of the Court of Québec hears criminal cases dealing with less serious offences and cases where the accused chooses to be heard by a judge alone instead of a judge and jury. It also deals with cases involving penal laws other than the Criminal Code.

The Youth Division hears cases of adoption and youth protection and criminal cases where the accused was a minor when the offence took place.

Superior Court

The Superior Court decides cases worth $100,00 or more. It can also decide cases worth between $75,000 and $100,000 (the person who initiates the proceeding may choose between

the Court of Québec and the Superior Court). It is the only court able to decide injunctions, class actions and anything that the Code of Civil Procedure qualifies as an “extraordinary recourse” (habeas corpus, prohibition, etc.). It hears all cases of divorce and bankruptcy and cases that are not assigned to another court.

The Superior Court also hears criminal and penal cases. Jury trials are held there and so are trials for serious crimes (e.g., murder, attempted murder, high treason).

Finally, the Superior Court acts as an appeal court for decisions in cases of less serious offences. Only this court can hear an “evocation” case (called judicial review, certiorari or revision), where the court can reverse a decision of a tribunal, public institution or professional corporation that has exceeded its powers.

Federal Court

The Federal Court hears cases dealing with matters which are federal government responsibilities under the Canadian Constitution. It hears appeals from decisions of some federal government bodies. It also decides disputes between provinces, or between provinces and the federal government. It hear claims between an individual or business and Canada and deals with specific subjects, like immigration, copyright, patents, taxes and admiralty.

The Human Rights Tribunal

The Human Rights Tribunal hears cases dealing with discrimination, harassment or exploitation under the Quebec Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms. The Tribunal has its own judges but it uses the clerks and location of the Court of Québec.

Not everyone can bring case to The Human Rights Tribunal. The Commission des droits de la personne et des droits de la jeunesse (Quebec human rights commission) decides which complaints to bring to the Tribunal. The advantage is that the Commission pays the fees!

Appeal Courts

These courts hear appeals from decisions of the courts of first instance. There are usually no witnesses. Only points of law are debated.

In Quebec, the appeal courts are the Federal Court of Appeal, the Court of Appeal of Québec and the Supreme Court of Canada.

Federal Court of Appeal

The Federal Court of Appeal hears appeals from some Federal Court decisions. It also deals with requests for judicial review of decisions of federal agencies like the CRTC.

Court of Appeal of Québec

The Court of Appeal of Quebec hears appeals from decisions of the courts of first instance. Note that decisions of the Federal Court can only be reviewed by the Federal Court of Appeal. Also, decisions of the small claims court cannot be appealed.

But not all decisions can be appealed. Only some decisions can be automatically appealed. In other cases, you must ask permission.

To win, the appellant has to convince the judges of the Court of Appeal that the first judge made a mistake of law or made conclusions about the facts that the evidence doesn’t support (decisions that were clearly not justified). The other party (the respondent) has the right to argue the opposite.

The Court of Appeal of Québec can also decide controversial questions of law, called a reference. Sometimes the courts of first instance have different opinions on a question of law (for example, how a law should be interpreted). The Court of Appeal decides the matter.

Supreme Court of Canada

The Supreme Court of Canada is composed of nine judges and is the final court in the land. Except for some criminal cases, you need permission to bring an appeal here. This permission can be given after reviewing the file without the people involved going to Ottawa.

The Supreme Court hears appeals from decisions of provincial or territorial appeal courts and the Federal Court of Appeal. It decides provincial references and questions submitted by the federal government (e.g., the reference on the secession of Quebec and the reference on same-sex marriage).

History of the Quebec Judicial System

1608

The governor of New France has total authority over the new colony. He can enforce laws and solve conflicts, among other things.

1639

Courts are created. Judges still have less authority than the governor, who has ultimate power. Certain lords apply “local justice” on their land.

1663

The Sovereign Council, where Jean Talon served, is the highest tribunal in the colony. It applies the “Coutume de Paris”. Legislative, judicial and executive powers have not yet been separated. Certain cases can be appealed to Parliament in Paris, but the governor is still the ultimate authority.

1760-1763

Surrender of New France to the British and beginning of a military regime. French civil law continues to apply to relations between individuals, but martial (military) law is applied in criminal matters.

1763

Treaty of Paris. New France becomes the province of Quebec and English law applies.

1774

The Quebec Act recognizes the French language, Catholic religion, and French law in civil matters. English law continues to apply in criminal cases.

1793

Lower Canada is divided into three judicial districts (Quebec, Montreal and Trois-Rivières). The courts are reorganized into provincial courts and “circuit courts.”

1843

A new law makes judges independent of the power of the executive. From then on, a judge may not be elected as a government representative or take part in making laws.

1849

Creation of the Barreau du Québec (Quebec bar).

1866

Adoption of the Civil Code of Lower Canada, which summarizes the French-inspired civil law that applies in Lower Canada (today the province of Quebec).

1867

Canada becomes a country. The new British North America Act (the Canadian Constitution) outlines the powers of the provinces and of the new central government. The two levels of government can only make laws on subjects that are under their power.

1870

Creation of the Chambre provincial des notaires, the predecessor of today’s Chambre des notaires du Québec (professional association of notaries).

1875

Creation of the Supreme Court of Canada

1965

Quebec becomes the first province to have a Department of Justice separate from the Department of Public Safety.

1971-1972

Quebec undergoes social reforms. The Small Claims Division and Legal Aid are created.

1976

The Quebec Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms becomes law. It recognizes the fundamental rights and freedoms that every person has. It also prohibits discrimination.

1980

The first Civil Code of Québec becomes law. It fundamentally reforms family law in Quebec.

1982

The Canadian constitution is repatriated. This means Canada no longer needs the consent of Britain to make laws and amend the constitution. The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms guarantees respect for individual rights and freedoms.

1988-1989

The Provincial Court, the Cour des sessions de la paix, the Youth Court and the Expropriation Court merge into the Court of Quebec.

1994-1996

New Civil Code of Québec comes into force. Legal Aid is reformed. The Act respecting administrative justice is adopted. The procedure for cases involving less than $50,000 is simplified.

2016

Reform of the Code of Civil Procedure. Formal requests to the courts are consolidated and case management is simplified.